Our kitchen’s being remodeled. By 7:15 Friday morning, there were three workers in that small place. At one time, seven men, six workers and me, crowded there. As the day wore on, three more came and went. The last carpenter left at 7:20 that evening.

Through the day, I took and made phone calls finalizing plans for Bethlehem, New Orleans benefit banquet. It was a fabulous evening. Larry and Patti, along with their friends Laurie and Bill, played terrific jazz. Yatz restaurant provided great Cajun food. Pastor Patrick Keen inspired us all. Generous Christians from across the Indianapolis conference donated upwards of $8,000 to support that mission.

Frazzled by the day and jazzed up by the evening, I couldn’t sleep. At midnight, still tossing and turning, I turned on Charlie Rose thinking some boring talk might lull me to sleep. It didn’t occur to me to play a tape of one of my sermons.

Charlie’s first guest was comedian, Bill Maher. Maher’s riffs against the president meant no sleep for me, yet! The second guest was a British author, Christopher Hitchins. Here, I thought, is a fast-acting sedative.

In his intro, Charlie spoke of Hitchens’ latest books. The first, he said, praised Thomas Jefferson for taking a razor to the New Testament and editing out the miracles. That left, Hitchins says, Jesus as philosopher and moral teacher. A second book was, The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice. I have no clue!

Charlie then said, “You’ve never been a fan of believers of any sort. Why am I not surprised by the title of your latest book, God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything?” I rushed downstairs to finish watching the show. Finally, in bed again at 1:15, I still tossed and turned. This time arguing with Hitchins where I thought he has it wrong and fighting with myself over what I have to admit Hitchins has right.

At one level, Hitchins doesn’t say anything new. Way back in 1711, Jonathan Swift, who authored Gulliver’s Travels, wrote, “We have just enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one another.”

Both Christopher Hitchins and Jonathan Swift are onto something. Each of them, though, misses the richness of the banquet table’s food, by focusing mostly on the corruption of those who:

• operate the hall

• select the ones to be invited as guests

• serve the diners

• as well as, how some of the welcomed diners behave both before and after the meal.

This, too, is nothing new.

Before we heard Jesus’ instruction to his disciples at their last supper together, in John 13:31-35 we heard Peter’s testimony about how God worked through Peter’s dream and Peter’s following through on that dream, for the benefit of Cornelius and his whole household, in Acts 11:1-18. I’m using the word, “testimony” not to describe Peter’s inspirational witness of faith. Testimony is the most accurate word because this event, happening not more than a few weeks or months after Jesus’ ascension, is the New Testament’s first recorded church fight and heresy trial. I find that to be way cool!

What’s cool isn’t the fight, obviously. What’s cool is that God inspired the believers who experienced it to record the whole messy event for our benefit. See, it never occurred to them that we might hear a story like this and find it to be poison.

Hitchins says religion poisons everything because so many believers hold that by obeying a few simple rules and holding some rather bizarre ideas, they will be rewarded with everlasting life in heaven. We’d have a hard time arguing his point. And if he’s completely correct, we’d also have to wonder why Bear and Lilly not only support this step we celebrate in Sarah’s and Paul's faith walk, they encourage it.

Here’s where Hitchins has it right. Religionists, then and now, work overtime to turn who the Bible says God is, and what this God does, on its head. Here’s where Hitchins has it wrong. Being Christian, becoming Christ-like, doesn’t have to make you a religionist.

What makes it hard to argue against Hitchins is that it often looks like there’s more evidence for his conclusion than there is for mine, for ours, for what Jesus commanded us to be and to do: By this will everyone know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another.

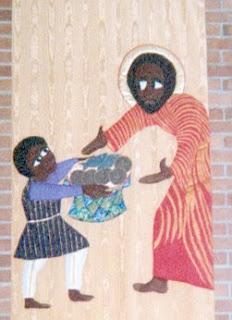

Today, in this banquet hall, where everyone is welcome as guest, we inept discipling, caterers are serving a rich food and drink to Sarah and Paul for the first time. Whatever it is we have not done before this meal, whatever it is we may fail to do after we’ve eaten, doesn’t change the One who is this Meal’s true Host. Nor does our doing or not doing change how Jesus, as our Host and this table’s food and drink, can transform Sarah and Paul, as well as us.

What God has in mind at this meal, what’s going on in Jesus’ heart in this meal, is that we become nourished and strengthened to join what God always does, what Jesus accomplished in his life, by his death, and now in his resurrection. Namely, that we might have life, and have it so abundantly that we, like Jesus, will give it away. We’re called to give our life away not as burden, or as a test, not as sacrifice, but as rich grace, as priceless, costly gift, from one beloved to another.

Martin Luther’s insight here, against religionists, with whom we still differ, is this. Eligibility for belonging in this body, criterion for welcoming by disciples of Jesus, entitlement for table service from the likes of us is not a reward for right rule keeping.

This banquet, as Jesus commanded it, is not open only to those who can afford a ticket. This dine-in experience is neither repayment for holding correct beliefs, nor is this an incentive for a promised place in heaven. Rather, the talk, the action, the visioning, the dreaming of rootednesses, relatedness, belonging and becoming in God start here, at this simple meal, the foretaste of the feast to come.

What God desires, what Jesus longs for, is that we become what we eat: breaking open persons, a pouring out people. What God desires, what Jesus promises, is that we who maintain this hall prepare and share this meal with all those whom God loves, keep on listening to God still speaking. That’s what obeying commands means – listening to God still speaking, following God still loving. That’s a far cry from the poison pill that makes folk run roughshod over people for the sake of rule keeping.

This morning, in their young faith, Sarah and Paul move beyond what they can see, and touch, and taste to listen to the command and to trust the promise that, somehow, Jesus is in this bread and in this wine, for each of them, for all of us. That’s, in part, a testimony to what they’ve seen as our faithful listening and trusting.

As their dining here continues, those of us more mature in faith, now get to model something else for Sarah and Paul. We can show them that it’s possible and desirable to move into and through what we see, and touch, and taste, to believe that despite the inept things we do before we eat, the God who is the true host of this table, remains truly for us. We can show them that by this eating and drinking, regardless of those corrupt things we do after we eat; this God still desires the kind of intimacy with us that nourishes us toward becoming Christ-like, out there.

Here’s a simple prayer to keep us all alert for God’s doing that and make us all acute to hearing that godly-call: God is great. God is good. Let us thank God for our food. Amen.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

I really enjoyed reading this post--Thanks!

Jeanne

Post a Comment