Someone asked me to stop by her house Friday to check out an electrical problem. I should say it was a simple electrical problem. In about three minutes I was only able to verify what she already knew, then give her the name of an electrician I know.

As I made my way toward the door, she asked me to look at a broken drawer in the kitchen. Next, she wanted me to see a problem with a towel rack in the bathroom. After that, it was the non-starting vacuum cleaner. Finally, as I headed again for the door, for sure this time, she blocked my way and began sobbing.

She needs to spend two weeks in the hospital, but doesn’t know where to send her children. Her uncle is being discharged from a nursing home but has nowhere to live. It was obvious the woman is overcome with dread. She’s terrified.

The dictionary’s definition of terror is “an overwhelming fear.” It’s a noun, not a verb.

I’m not sure how you’d launch and sustain a war on terror. For that matter, I have no idea how one would launch and sustain a war drugs or a war on poverty – much less with those wars. I also don’t understand how greed seems to drive contestants on the TV show, “Fear Factor,” strengthens them to do what they do. What I do know is the two most common responses to overwhelming fear, among humans and even in the lowest forms of animal life, are fight or flight.

Brain research shows that those instincts reside in the most primitive part of the human brain. Located just above the part of our brain that keeps us breathing, this unsophisticated body part is called the reptilian brain. It requires neither thinking nor decision-making (higher brain functions) for the reptilian brain to become engaged and initiate the fight or flight response.

We also know that, using our higher brain, the cerebral cortex, humans are one of the few species that can bring fear onto ourselves. All we have to do is remember something or someone that frightened us yesterday, or imagine someone or something threatening us tomorrow, and boo; we’re scared.

More than that, we use still higher levels of brainpower to bring on what I’ll call conceptual fear to ourselves. Maybe you’re afraid of becoming senile. Maybe you fear a diagnosis of cancer. Perhaps you’re frightened you’ll lose your job, be mugged, walk into your house during a burglary, lose a child, become addicted to drugs or alcohol, be divorced, never find the right mate, or be abused by your mate. If any of that has already happened to you, you might still be carrying that fear with you in the present, as well as throwing that terror ahead of you, into your future.

Some of us are not only afraid of dying; we fear being dead. Others of us fear that the world will, or may, end. Many are also afraid both of being here when that happens, and/ or what will, or may, happen to them after that happens, even if they get their wish and are dead when that happens.

I want to suggest that much of this latter fear, the terror we associate with the so-called end of the world, is as manufactured as are our silly superstitions. A mix of both our higher and lower brains invents these practices. It’s a cross between our intellectual desire to control environments and events, as well as our feeling-fueled, magical thinking that some incantation or charm can stop forces we believe to be beyond our control. Like our superstitions, the fears we have and cultivate about the end of the world, or the end-times, are something we acquire by bad teaching.

Maybe we can God’s word to us in Psalm 16 and Mark 13:1-13 to experience what God’s word always intends, namely, grace.

Now, there’s a lot more than fear and superstition going on in this conversation between Jesus and his four most trusted disciples. There’s even more going on in the statement Jesus makes about the Temple, “…not one stone will be left on another.” To be sure, what Jesus said caused no small measure of terror in those who heard it then as well as those who’ve read it since. However, a good measure of that terror, as well as the fight or flight responses the terror has set off, is misplaced.

Right off the bat Jesus is saying, the world is not a secure place and, you ought not to bet the farm on those in charge of running it. He says this sitting opposite the Temple – not just across from the Temple, but also in opposition to the Temple.

Both the government officials, as well as the religious officials, have set up shady systems on what was already shifting sands. That reality wasn’t new news then, and it isn’t new news now. Still, it shook these disciples to their core. If the most significant sign of their identity as God’s chosen people was destroyed, could they continue to name and claim that identity.

Jesus continues to explain himself, implying that even within what would become the community of his followers, they, too, could construct the same shady systems. That, too, could hardly be new news to folks who’d experienced the kind of arguing and jockeying for position that these four had been part of. It’s not new news to us either, is it?

Jesus says when the insecurities of world are most apparent, when the shady systems are most oppressive, that’s not the end. Now, “end,” here doesn’t mean finale, it means full purpose or complete accomplishment. Jesus never says, “I know something you don’t know, it’s all gonna crash and burn.” He does say, this will all pass, through pain that’s as excruciating as maternal labor, and new birth will result – God’s full purpose, God’s complete accomplishment. You may not like the travel, but you’re gonna be thrilled with the destination.

For all that, the fear can be overwhelming, a terrible terror. In that emotional space, people of faith, those who’ve stood with Jesus opposite all manner of powers and principalities, have done much more than tear and tremble.

They have, like the psalmist, or like John in Revelation, used poetry, lyric, even fantasy, (that doesn’t mean bull-loney, it means imagination and allusion and metaphor) to enter into the terror. It’s neither fight, nor flight. It doesn’t come from sheer intellect. Neither does it rise from brute force. It wells up from deep within, sometimes we call it soul – that place where God speaks to us, each, a special name; holds us close in God’s own holy palms; and, lifts us up and calms us down with God’s own soothing breath.

Look at the godly, life-giving power of this ordinary language the Psalmist composes in Psalm 16.

Protect me, O God, for in you I take refuge.

2I say to the LORD, "You are my LORD;

I have no good apart from you."

3As for the holy ones in the land, they are the noble,

in whom is all my delight.

4Those who choose another god multiply their sorrows;

their drink offerings of blood I will not pour out

or take their names upon my lips.

5The LORD is my chosen portion and my cup;

you hold my lot.

6The boundary lines have fallen for me in pleasant places;

I have a goodly heritage.

7I bless the LORD who gives me counsel;

in the night also my heart instructs me.

8I keep the LORD always before me;

because he is at my right hand, I shall not be moved.

9Therefore my heart is glad, and my soul rejoices;

my body also rests secure.

10For you do not give me up to Sheol,

or let your faithful one see the Pit.

11You show me the path of life.

In your presence there is fullness of joy;

in your right hand are pleasures forevermore.

That’s all I could do for the dread-filled woman on Friday. I held her close. Leaned my cheek against hers, and whispered in her ear, over and over, “Breathe, Sister. God will get us through. You don’t have to go alone. We’re here with you.”

I never said I would, or we would, make it better. I didn’t even say that God would fix it. I did only what we do here, as followers of Jesus, trying to avoid constructing a shady system, seeking always to avoid banking on the insecurity of this world’s shifting sands.

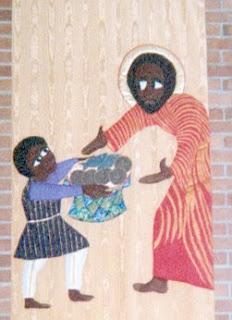

I drew that from what a worshipping assembly gave me last Sunday, what I know they’ll have for me each time we gather and celebrate together the Lord’s Supper. See, we do here what Jesus’ followers have been doing since their world ended on Good Friday, and their terror drove them to a locked room on Saturday.

Each week, on the same day of the week that they met the risen Jesus, the one who said, “Peace be with you,” we stand in opposition to shady systems, and testify that our security does not come from this world. We face each other, one by one, reaching out to one another in the name of the source of our courage, standing firmly on the promise of the one who transforms world.

Newcomers might think our practice is chaotic. Even some of us may see it as a kind of commercial break, a chance to catch up. But it’s much more than that.

See, each of us has occasions to stand with someone out there who’s overwhelmed by fear, terrified. I also know that people treat religious officials like good luck charms, always ready to deliver a magical incantation to make everything all right. You know different, because you’ve done what I did last Friday.

It’s not the verse you quote that stands in opposition to terror, it’s the vigor of your voice that testifies to God’s otherwise. It’s not the melody of the song you sing that faces fear down; it’s your confidence in the lyric-maker helps you endure to the end, to God’s accomplishing desire. Where does that come from?

From your tender touch, in the graceful gaze of your eyes, with your breath-filled confident claim and blessing called down, “The peace of Christ be with you,” we draw strength and courage to face terror head on, and walk right into it.

Last Friday, everyday we rely on that Holy Spirit, there was no fight. There was no flight. No charm, not a single incantation, just breath, a simple claim, a powerful blessing: “It’s OK. God will see us through.” Nothing was changed and everything is new.

Monday, November 20, 2006

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment