My seminary professors suggested I find a model, using a character from the Bible, to give form and shape to my Christian identity. It's a good idea. Through prayer; by inventorying your talents; discovering your passions; and in conversation with friends; it's possible for all of us to find a biblical character or role to imitate. You might be drawn to:

• Jesus the teacher or Jesus the healer

• Esther, the real power behind the throne

• Mary, the meditative pray-er

• Zaccheus, the repentant crook

• Joseph, (either Genesis or Luke) the crisis manager

• Martha, the never say no over-achiever.

The strategy is a sound way to experience what we call sanctification - a deepening relationship with God. As Saint Paul says, we can experience progress and joy in faith because we live lives worthy of the Gospel.

Growing up in the sixties, seeing racial injustice and the horrors of war in Viet Nam, I found a model that works for me. I've always felt drawn to the motives and actions of biblical prophets. Their motivation was to remind people of: God's faithfulness to us; God's love and care for us; God's desire for a just future for all people; and, God's reign of shalom over the universe.

The prophets seem to have achieved this by: comforting the disturbed and disturbing the comfortable. There's also the idea that the roles Jesus used to declare and make present his vision of the reign of God was to act as priest, prophet and king. Some people recognize that all those baptized into the mission and ministry of Jesus must come to understand our identity and our roles that way.

Not only does the prophetic model suit my talents and my temperament, a way of seeing and acting that I'm drawn to and good at, it also seems to be a role that others call on me to perform. In most jobs, I've been a builder and a fixer. As a pastor I must analyze how our community of faith is organized; what's really getting done as opposed to what's supposed to be getting done. It's made me learn to pay attention to how each of us is functioning. Are we thriving as persons? Do we feel honored and cherished? As a group are we cooperating, supporting one another, challenging each other? Is this a congregation in which it's OK to take risks? If a person fails or a project misfires can we move on? Or do we sow doubt; practice distrust; count things against one another; carry tales; hold grudges? What holds us together? Are we operating from a clear consensus about strategies to achieve God's mission, or do we promote personal anxiety and corporate discontent when the compromises we reach create winners and losers?

Well, no matter how skilled and clever we are inside of our ministry model, we are, as Luther frequently points out, simul justus et peccatur, at once saints and sinners. And because of that, achieving the balance between the role shaping us, and our shaping the role can be tough.

That's a lesson we can't be sure Jonah ever learned (read especially 3:10-4:11). And we can use the fact that we're not sure he learned it to assess just how well we've learned it. Maybe I'm not the only one who could use a refresher course.

Prophets are often described as angry. We see that in our own day when advocates for justice demand that the United States send troops to stop ethnic cleansing. They use blistering words to goad our leaders out of paralysis by analysis and into decisive action. There is such a thing as righteous indignation and holy anger.

In a similar way the anger of Jeremiah or Amos was rooted in a love for God and love for the very people who were the object of their wrath. Their aim wasn't personal vindication but the vindication of God's truth and justice, by Israel's conversion to the same sort of faithfulness God had extended to the chosen people. If the prophets saw more clearly than other folks that Israel's real choice was life or death, their hope and prayer was that the people would choose life. And so their words -sometimes spoken angrily - at other times in heartbroken sobs - were directed to that end. Their witness wasn't motivated by anger, but by love.

But then there is a prophet like Jonah. He found his mission so unpleasant that when the word of God came to him to bear witness against Nineveh, he fled in the other direction. Now we all remember the unusual taxi ride by which Jonah got heaved up on the beach, but we don't always remember the lone sermon he delivered to the Ninevites. In all the woe sayings; the oracles; the judgments; we hear from the prophets, Jonah's stands as the most lame. It goes like this, "Forty days more and Nineveh shall be overthrown."

Amos called Israel's women "cows of Babylon." Ezekiel called Israel "unfaithful harlots." Hosea called Israel a "temple prostitute." So Jonah's words lack the passion, not to mention the sincerity, necessary to get a whole country to change course. But Jonah's words have such an impact that the king and the nobles order even the animals to repent with fasting. So effective is Jonah's sermon that the people are thoroughly converted and receive God's forgiveness.

Is Jonah relieved? Uh-uhh. He's furious. And here we see the true source of Jonah's anger. Jonah is angry over God's mercy. That's why he got into the boat in the first place. He was afraid that his prophecy might work. He didn't want anything to do with a God who would let Nineveh escape what Jonah had determined was its just desserts. What kind of God is that? You can't predict what that kind o’ God is gonna do. You can't control a God like that. So God responds to Jonah's rage with a compassionate, almost parental question: "Do you do well to be angry?"

Like a two-year old child, Jonah storms off, putting distance between himself and God, once again. He goes outside the city, and builds an isolation booth, an outhouse, still hoping to see God's wrath blaze against Nineveh. But the only thing blazing is the scorching wind - in Hebrew - ruach. The same word used to describe God's breathing life, light and hope into every isolating booth, especially the one-person-tent we know as the unloving, unforgiving human heart - an outhouse of our own making.

Now we're not used to it, preachers don't help us see this often. But God does have a sense of humor. God's response to Jonah's tantrum, which has him all tangled up in knots; - has his bowels in an uproar - is to raise up a castor oil plant, at the threshold of this outhouse! It's as if God says,

"Get over it Jonah. Take a physic! This, too, shall pass!"

Like everything else, Jonah gets it wrong. He thinks the plant has more to do with his outsides than his insides. The only thing Jonah let's pass is another chance to see God's mercy and love. When the plant dies Jonah spins out of control. And God asks, "Do you do well to be angry for the plant?" Jonah replies on cue, "Angry enough to die." Jonah still can't stomach a merciful God. This is one angry prophet!

God tries to give Jonah some perspective. "OK, if you're willing to die for a castor oil plant, shouldn't I care for a whole city?" Do you see the contrast between Jonah's impotent, death-dealing rage and God's compassion - God's wombing the men, women and children back into life-giving relationship? God says, "Should I not pity Nineveh, a great city, in which there are more than 120,000 persons who don't know there right hand from their left, and also much cattle?"

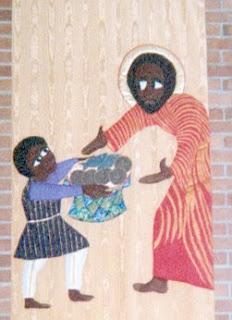

What's going on here isn't a story about Nineveh at all. It's a story of Jonah's own call to conversion. It's not enough to be an agent of God's anger. True prophets are called to be agents of God's love.

"Do you do well to be angry?" It's not whether Jonah's anger is justified. We all have cause to be angry sometimes, but does our anger do well? Does anger do anything but feed our sense of being absolutely right and our enemies absolutely wrong? Feeling that way, don't we get a kind of high by going off into some fantasy-land where we see ourselves heroically showing the whole world just how right we are? But do fantasies bring conversion, prompt reconciliation, or add an ounce of justice to the world?

We would rather vent our anger than convert enemies into friends. Often our words and actions suggest that the very last thing we want is for our enemies to admit they're wrong and change their ways. Convinced that we are agents of God's justice, we eagerly deliver a word of judgment. We're quick to pronounce the death sentence. We're not so eager to deliver the merciful words of clemency and relationship.

The story of Jonah's call to conversion reminds us of the many ways we prefer our ways over God's ways. We:

• flee to the east when God would have us go west

• run outside the city gates

• build us a one-person-tent to isolate our angry heart.

Jonah's call to conversion reminds us it's not enough to be an agent of God's anger. Anger may be necessary to point out a problem, but anger is never sufficient to birth a solution. There are many causes for anger in this world. But God's mercy isn't one of them.

What are we afraid of? What part of God's care for us and for this world do we think we have to predict? Do we think we should control God's care and love and mercy? What fears do we have of God that make us angry with God?

That's what the story of Jonah is all about. Do we do well to be angry? It doesn't matter. The good news is that, angry as we are, God's mercy extends to us as well:

• that might mean gettin' thrown overboard

• that might feel like bein' swallowed up by a monster

• it could come to gettin' coughed up onto a beach

• we may even look washed up and rung out.

It doesn't matter. This God is always for us. This God creates us in love, redeems us in Christ and sends the Spirit to call and gather us, alone and together, to join in telling others that same, simple Good News: "Look, I got myself all scared and angry and bound up, then this God sent me a castor oil plant and I got over it. God will help you get over it too!"

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment